NonConvex Quantum Characterization

This project is supported by NSF (CCF:FET 1907936)

Collaborators:

Anastasios Kyrillidis (Rice CS - PI)Amir Kalev (USC CS)

Georgios Kollias (IBM NY)

Jay Gambetta (IBM NY)

Students:

Junhyung Lyle Kim (Rice CS)

David Quiroga (Rice CS)

This blog post is about our initial work on quantum state tomography using non-convex programming.1 This manuscript is on arXiv, but also published at npj Quantum Information. This is a joint work of Prof. Tasos Kyrillidis at Rice University, Dr. Amir Kalev at USC, Dr. Dohyung Park, Dr. Srinadh Bhojanapalli, Prof. Constantine Caramanis and Prof. Sujay Sanghavi.

Introduction

Like any other processor, the behavior of a quantum information processor must be characterized, verified, and certified. Quantum state tomography (QST) is one of the main tools for that purpose2. Yet, it is generally an inefficient procedure, since the number of parameters that specify quantum states, grows exponentially with the number of sub-systems.

This inefficiency has two practical manifestations: \((i)\) without any prior information, a vast number of data points needs to be collected2; \((ii)\) once the data is gathered, a numerical procedure should be executed on an exponentially-high dimensional space, in order to infer the quantum state that is most consistent with the observations. Thus, to perform QST on nowadays steadily growing quantum processors, we must introduce novel, more efficient, techniques for its completion.

To improve the efficiency of QST, we need to complement it with numerical algorithms that can efficiently handle large search spaces using limited amount of data, while having rigorous performance guarantees. This is the purpose of this work. Inspired by the recent advances on finding the global minimum in non-convex problems3 4 5 6 7 8, we propose the application of alternating gradient descent in QST, that operates directly on the assumed low-rank structure of the density matrix. The algorithm –named Projected Factored Gradient Decent (ProjFGD)– is based on the recently analyzed non-convex method3 for PSD matrix factorization problems. The added twist is the inclusion of further constraints in the optimization program, that makes it applicable for tasks such as QST.

Problem setup

We begin by describing the problem of QST. We are focusing here on QST of a low-rank \(n\)-qubit state, \(\rho_{\star}\), from measuring expectation values of \(n\)-qubit Pauli observables \(\{P_i\}_{i=1}^m\). We denote by \(y \in \mathbb{R}^m\) the measurement vector with elements \(y_i = \tfrac{2^n}{\sqrt{m}}\text{Tr}(P_i \cdot \rho_\star)+e_i,~i = 1, \dots, m\), for some measurement error \(e_i\). The normalization \(\tfrac{2^n}{\sqrt{m}}\) is chosen to follow the results of Liu9. For brevity, we denote \(\mathcal{M} : \mathbb{C}^{2^n \times 2^n} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\) as the linear “sensing” map, such that \((\mathcal{M}(\rho))_i = \tfrac{2^n}{\sqrt{m}} \text{Tr}(P_i \cdot \rho)\), for \(i = 1, \dots, m\).

An \(n\)-qubit Pauli observable is given by \(P=\otimes_{j=1}^n s_j\) where \(s_j\in\{\mathbb{1},\sigma_x,\sigma_y,\sigma_z\}\). There are \(4^n\) such observables in total. In general, one needs to have the expectation values of all \(4^n\) Pauli observables to uniquely reconstruct \(\rho_\star\). However, since according to our assumption \(\rho_\star\) is a low-rank quantum state, we can apply the CS result10 9, that guarantees a robust estimation, with high probability, from the measurement of the expectation values of just \(m={\cal O}(r 2^n n^6)\) randomly chosen Pauli observables, where \(r\ll 2^n\) is the rank of \(\rho_\star\).

For the compressed sensing quantum state tomography setting, requires the following pivotal assumption on the sensing matrix \(\mathcal{M}(\cdot)\), namely the Restricted Isometry Property (RIP) (on \(\texttt{rank}\)-\(r\) matrices): 11

\begin{align} \label{eq:rip} \tag{2} (1 - \delta_r) \cdot || X ||_F^2 \leq || \mathcal{M}(X) ||_2^2 \leq (1 + \delta_r) \cdot ||X||_F^2. \end{align}

The above condition should hold for all low-rank \(X\) matrices. Intuitively, the above RIP assumption states that the sensing matrices \(\mathcal{M}(\cdot)\) only “marginally” changes the norm of the matrix \(X\).

QST as an optimization problem

An accurate estimation of \(\rho_\star\) is obtained by solving, essentially, a convex optimization problem constrained to the set of quantum states12, consistent with the measured data. Among the various problem formulations for QST, two convex program examples are the trace-minimization program that is typically studied in the context of CS QST:

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

& \underset{\rho \in \mathbb{C}^{2^n \times 2^n}}{\text{minimize}}

& & \text{Tr}(\rho)

& \text{subject to}

& & \rho \succeq 0,

& & & ||y - \mathcal{M}(\rho)||_2 \leq \epsilon,

\end{aligned} \label{eq:CVX1}

\end{equation}

and the least-squares program,

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

& \underset{\rho \in \mathbb{C}^{2^n \times 2^n}}{\text{minimize}}

& & \tfrac{1}{2} \cdot ||y - \mathcal{M}(\rho)||_2^2

& \text{subject to}

& & \rho \succeq 0,

& & & \text{Tr}(\rho) \leq 1,

\end{aligned} \label{eq:CVX2}

\end{equation}

which is closely related to the (negative) log-likelihood minimization under Gaussian noise assumption. The solutions of these programs should be normalized to have unit trace to represent quantum states.

Projected Factored Gradient Descent

At its basis, the Projected Factored Gradient Descent (\(\texttt{ProjFGD}\)) algorithm transforms convex programs by enforcing the factorization of a \(d\times d\) PSD matrix \(\rho\) such that \(\rho = A A^\dagger\), where \(d=2^n\). This factorization naturally encodes the PSD constraint, removing the expensive eigen-decomposition projection step. In order to encode the trace constraint, \(\texttt{ProjFGD}\) enforces additional constraints on \(A\): the requirement that \(\text{Tr}(\rho) \leq 1\) is equivalently translated to the convex constraint \(\|A\|_F^2 \leq 1\). The above recast QST as a non-convex program:

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

& \underset{A \in {\mathbb C}^{d \times r}}{\text{minimize}}

& & f(AA^\dagger) :=~ \tfrac{1}{2} \cdot ||y - \mathcal{M}(AA^\dagger)||_2^2

& \text{subject to}

& & ||A||_F^2 \leq 1.

\end{aligned} \label{eq:nonCVX}

\end{equation}

While the constraint set is convex, the objective is no longer convex due to the bilinear transformation of the parameter space \(\rho = AA^\dagger\). Here, the added twist is the inclusion of further matrix norm constraints, that makes it proper for tasks such as QST.

The \(\texttt{ProjFGD}\) algorithm and its guarantees

At heart, \(\texttt{ProjFGD}\) is a projected gradient descent algorithm over the variable \(A\); i.e.,

\begin{equation} A_{t+1} = \Pi_{\mathcal{C}}\left(A_t - \eta \nabla f(A_t A_t^\dagger) \cdot A_t\right) \nonumber, \end{equation}

where \(\Pi_\mathcal{C}(B)\) denotes the projection of a matrix \(B \in \mathbb{C}^{d \times r}\) onto the set \(\mathcal{C} = \left\{ A : A \in \mathbb{C}^{d \times r}, ~||A||_F^2 \leq 1\right\}\). \(\nabla f(\cdot): \mathbb{R}^{d \times d} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}\) denotes the gradient of the function \(f\).

Our theory dictates a specific constant step size selection, \(\eta\), that guarantees convergence to the global minimum, assuming a satisfactory initial point \(\rho_0\) is provided. More details on the theory are provided in our paper1.

Results

First, we find that our initialization, as well as random initialization, works well in practice, and this behavior has been observed repeatedly in all the experiments we conducted. Thus, the method returns the exact solution of the convex programming problem, while being orders of magnitude faster than state-of-the-art optimization programs.

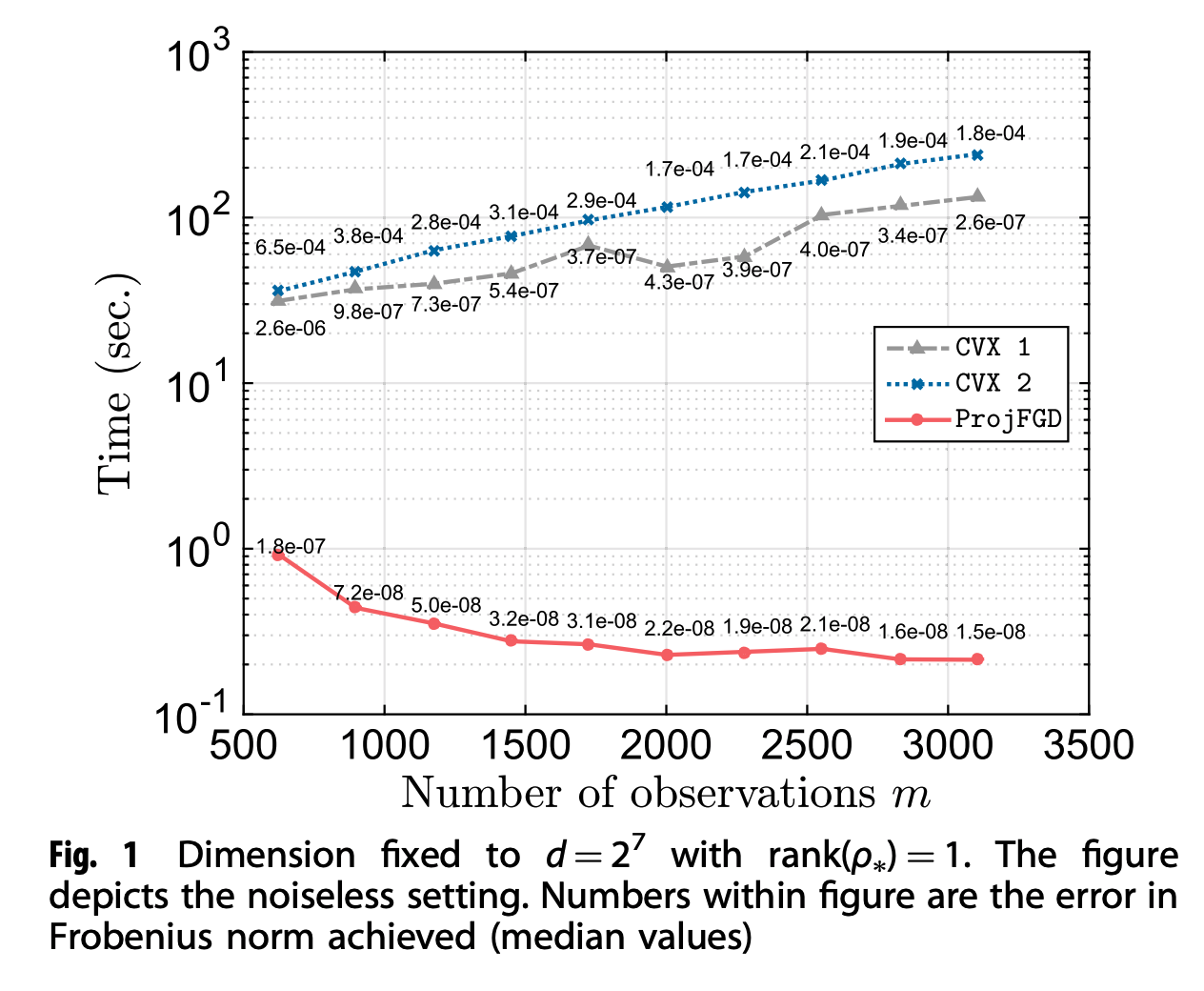

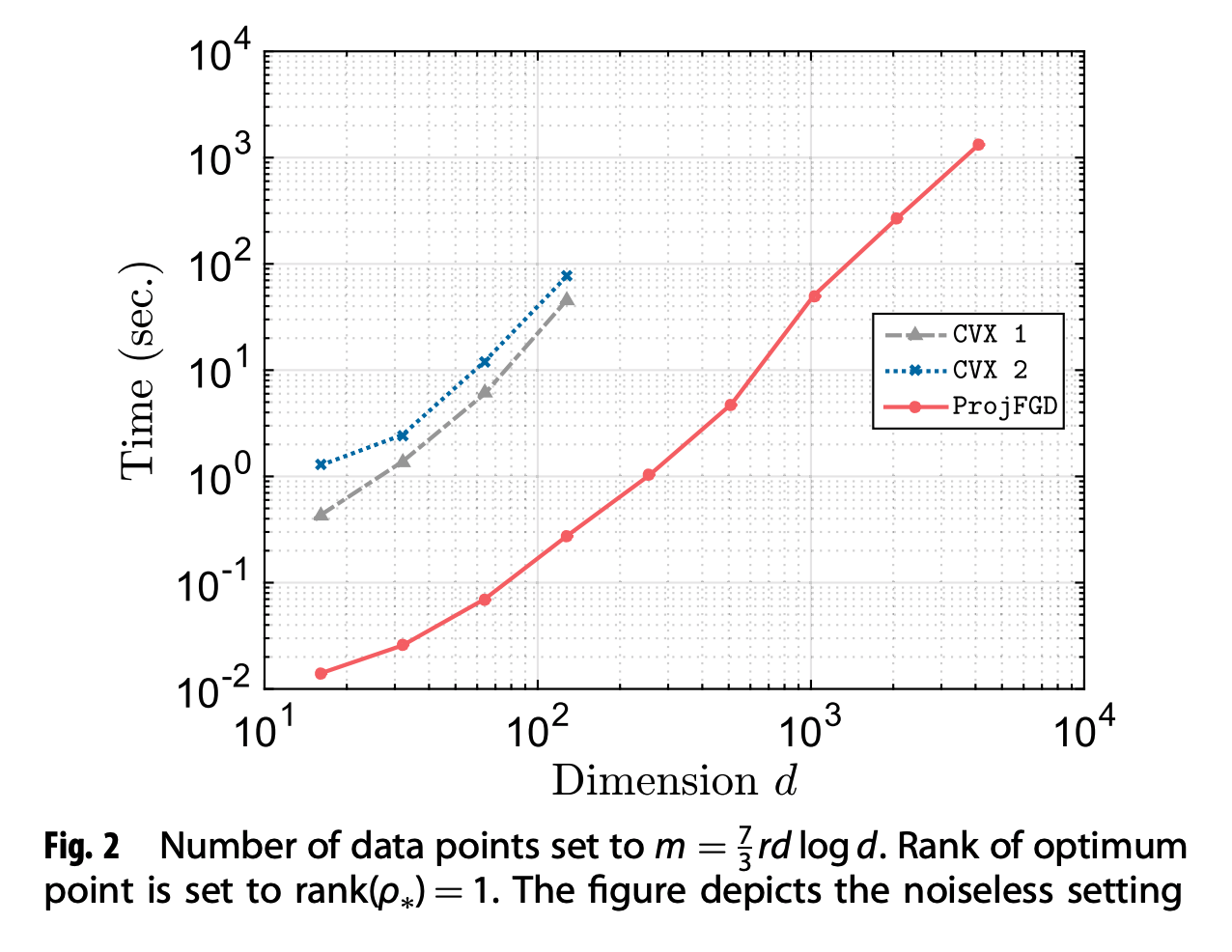

Efficiency of \(\texttt{ProjFGD}\) versus second-order cone programs

State of the art solvers within this class of solvers are the SeDuMi and SDPT3 methods; for their use, we rely on the off-the-shelf Matlab wrapper \(\texttt{CVX}\). In our experiments, we observed that SDPT3 was faster and we select it for our comparison.

The figures above show graphically how second-order convex vs. our first-order non-convex schemes scale. We observe that, while in the \(\texttt{ProjFGD}\) more observations lead to faster convergence, the same does not hold for the second-order cone programs. It is obvious that the convex solvers do not scale easily beyond \(n = 7\), whereas our method handles cases up to \(n = 13\), within reasonable time. We note that, as \(n\) increases, a significant amount of time in our algorithm is spent forming the Pauli measurement vectors \(P_i\); i.e., assuming that the application of \(P_i\)’s takes the same amount of time as in CVX solvers, \(\texttt{ProjFGD}\) requires much less additional computational power per iteration.

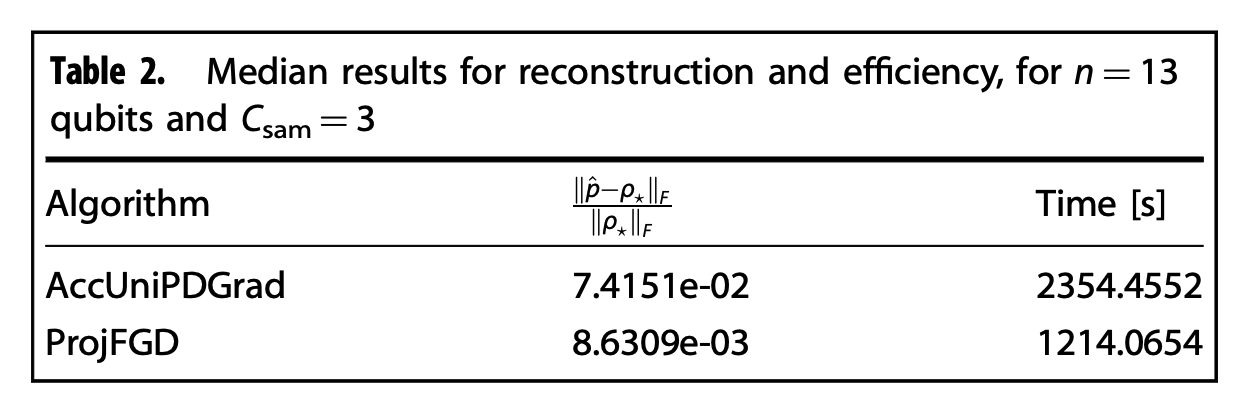

Efficiency of \(\texttt{ProjFGD}\) versus first-order methods

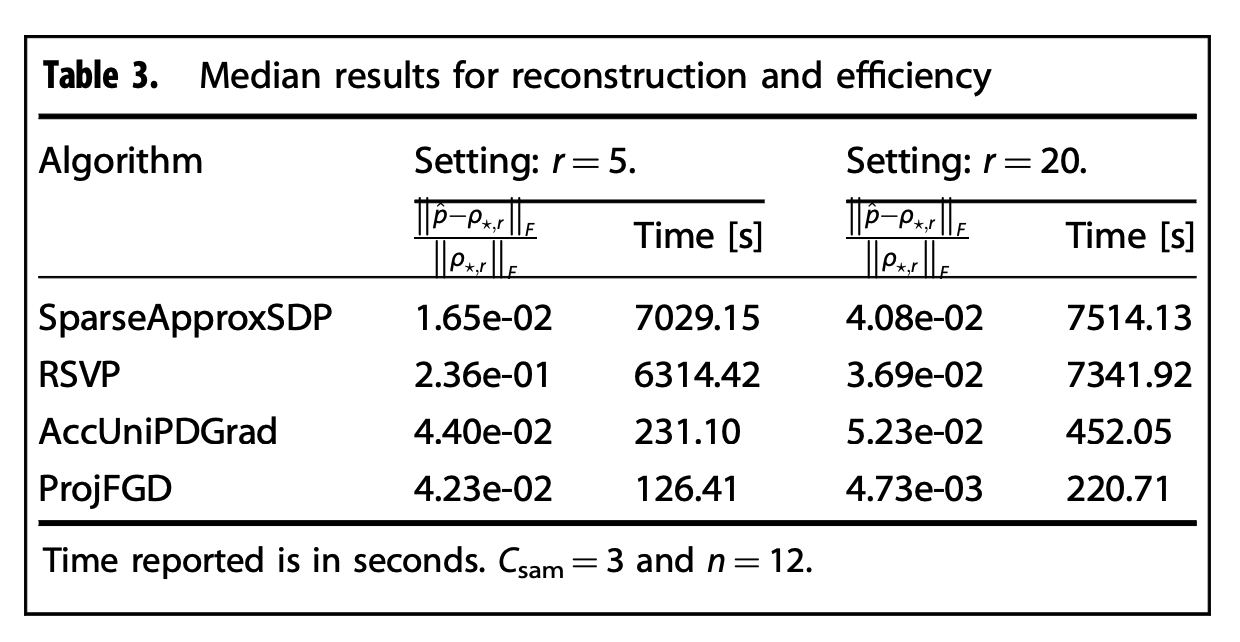

We compare our method with more efficient first-order methods, both convex (\(\texttt{AccUniPDGrad}\)13) and non-convex (\(\texttt{SparseApproxSDP}\)14 and \(\texttt{RSVP}\)15).

We consider two settings: \(\rho_\star\) is \((i)\) a pure state (i.e., \(\text{rank}(\rho_\star) = 1\)) and, \((ii)\) a nearly low-rank state. In the latter case, we construct \(\rho_\star = \rho_{\star, r} + \zeta\), where \(\rho_{\star, r}\) is a rank-deficient PSD satisfying \(\text{rank}(\rho_{\star, r}) = r\), and \(\zeta \in \mathbb{C}^{d \times d}\) is a full-rank PSD noise term with a fast decaying eigen-spectrum, significantly smaller than the leading eigenvalues of \(\rho_{\star, r}\). In other words, we can well-approximate \(\rho_\star\) with \(\rho_{\star, r}\). For all cases, the noise is such that \(||e||_2 = 10^{-3}\). The number of data points \(m\) satisfy \(m = C_{\rm sam} \cdot r d\), for various values of \(C_{\rm sam} > 0\).

The table above contains recovery error and execution time results for the case \(n = 13\) (\(d = 8192\)); in this case, we solve a \(d^2 = 67,108,864\) dimensional problem. For this case, \(\texttt{RSVP}\) and \(\texttt{SparseApproxSDP}\) algorithms were excluded from the comparison, due to excessive execution time.

The table above considers the more general case where \(\rho_\star\) is nearly low-rank. In this case, \(n = 12\) (\(d = 4096\)), \(m = 245,760\) for \(C_{\rm sam} = 3\). As the rank in the model, \(r\), increases, algorithms that utilize an SVD routine spend more CPU time on singular value/vector calculations. Certainly, the same applies for matrix-matrix multiplications; however, in the latter case, the complexity scale is milder than that of the SVD calculations.

Overall, \(\texttt{ProjFGD}\) shows a substantial improvement in performance, as compared to the state-of-the-art algorithms; we would like to emphasize that projected gradient descent schemes, such as in Becker et al.15, are also efficient in small- to medium-sized problems, due to their fast convergence rate. Further, convex approaches might show better sampling complexity performance (i.e., as \(C_{\rm sam}\) decreases). Nevertheless, one can perform accurate maximum likelihood estimation for larger systems in the same amount of time using our methods for such small- to medium-sized problems.

Conclusion

With nowadays steadily growing quantum processors, it is required to develop new quantum tomography tools that are tailored for high-dimensional systems. In this work, we describe such a computational tool, based on recent ideas from non-convex optimization. The algorithm excels in the compressed-sensing-like setting, where only a few data points are measured from a lowrank or highly-pure quantum state of a high-dimensional system. We show that the algorithm can practically be used in quantum tomography problems that are beyond the reach of convex solvers, and, moreover, is faster than other state-of-the-art non-convex approaches. Crucially, we prove that, despite being a non-convex program, under mild conditions, the algorithm is guaranteed to converge to the global minimum of the problem; thus, it constitutes a provable quantum state tomography protocol.

-

A. Kyrillidis, A. Kalev, D. Park, S. Bhojanapalli, C. Caramanis, and S. Sanghavi. Provable quantum state tomography via non-convex methods. npj Quantum Information, 4(36), 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

Altepeter, J., Jeffrey, E. & Kwiat, P. Photonic state tomography, advances in atomic. Mol. Opt. Phys. 52, 105–159 (2005). ↩ ↩2

-

Bhojanapalli, S., Kyrillidis, A. & Sanghavi, S. Dropping convexity for faster semidefinite op- timization. In 29th Annual Conference on Learning Theory, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 49, 530–582 (2016). ↩ ↩2

-

Chen, Y. & Wainwright, M. Fast low-rank estimation by projected gradient descent: general statistical and algorithmic guarantees. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1509.03025 (2015). ↩

-

Ge, R., Lee, J. & Ma, T. Matrix completion has no spurious local minimum, In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2973–2981 (2016). ↩

-

Park, D., Kyrillidis, A., Caramanis, C. & Sanghavi, S. Finding low-rank solutions to matrix problems, eficiently and provably. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.03168 (2016). ↩

-

Park, D., Kyrillidis, A., Carmanis, C. & Sanghavi, S. Non-square matrix sensing without spurious local minima via the Burer–Monteiro approach. In Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, 65–74 (2016). ↩

-

Sun, R. & Luo, Z.-Q. Guaranteed matrix completion via nonconvex factorization. In IEEE Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 270–289 (2015). ↩

-

Liu, Y.-K. Universal low-rank matrix recovery from Pauli measurements. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 1638–1646 (2011). ↩ ↩2

-

D. Gross, Y.-K. Liu, S. Flammia, S. Becker, and J. Eisert. Quantum state tomography via compressed sensing. Physical review letters, 105(15):150401, 2010. ↩

-

Benjamin Recht, Maryam Fazel, and Pablo A Parrilo. Guaranteed minimum-rank solutions of linear matrix equations via nuclear norm minimization. SIAM review, 52(3):471–501, 2010. ↩

-

A. Kalev, R. Kosut, and I. Deutsch. Quantum tomography protocols with positivity are compressed sensing protocols. NPJ Quantum Information, 1:15018, 2015. ↩

-

Yurtsever, A., Dinh, Q. T. & Cevher, V. A universal primal-dual convex optimization framework. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 3150–3158 (2015). ↩

-

Hazan, E. Sparse approximate solutions to semidefinite programs. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 4957, 306–316 (2008). ↩

-

Becker, S., Cevher, V. & Kyrillidis, A. Randomized low-memory singular value projection. In 10th International Conference on Sampling Theory and Applications (Sampta), 364–367 (2013). ↩ ↩2