Introduction to quantum computing: Bloch sphere.

Sources:

“Quantum computing for computer scientists”, N. Yanofsky and M. Mannucci, Cambridge Press, 2008.

This is part of a (probably) long list of posts regarding quantum computing. In this post, we will discuss about a very intuitive representation of a single qubit: the Bloch sphere. We will make connections of this diagram with quantum gates, like the Pauli matrices.

Disclaimer I: while the material below might seem too simple for some scientists, I suggest not skimming over this post - personally, I always enjoy reading something that I believe I own, as επαναληψη μητηρ πασης μαθησεως (repetition is the mother of any knowledge)

A different representation of qubits

The TL;DR version of this section is: given that qubits are connected to complex numbers, use imaginary complex sphere for their representation, and worry about angles and lattitudes.

Let’s see why is this the case. Consider the case of a quantum state:

\[|\mathbf{\psi} \rangle = c_0 \cdot |\mathbf{0} \rangle + c_1 \cdot | \mathbf{1} \rangle.\]Reminder: $|c_0|^2 + |c_1|^2 = 1$, where $c_i \in \mathbb{C}$. Using the polar representation of a complex number, we have the following two equivalent representations:

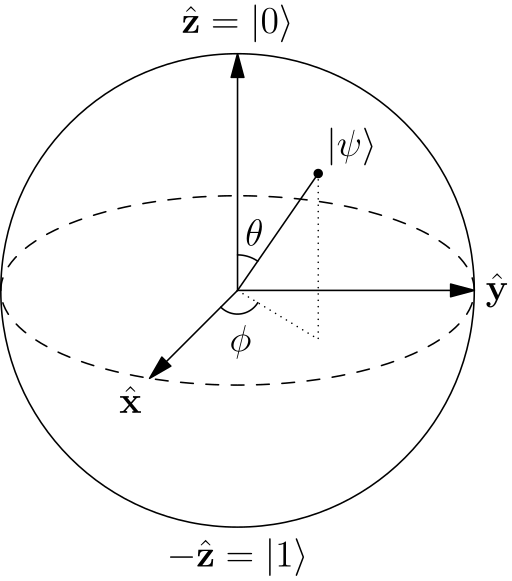

\[c_0 = r_0 e^{j\varphi_0} ~~\text{and}~~ c_1 = r_1 e^{j\varphi_1}\]where $r_i$ are the amplitudes and $\varphi_i$ are the angles. Thus, each individual number $c_i$ can be represented with a unit imaginary circle.

Thus, given we have two components $c_i$, one can conclude that we have 4 unknowns (2 phases and 2 amplitudes) that uniquely determine components. Using the above, our state can be re-written as:

\[| \mathbf{\psi} \rangle = r_0 e^{j\varphi_0} \cdot | \mathbf{0} \rangle + r_1 e^{j\varphi_1} \cdot | \mathbf{1} \rangle\]However, in the case of quantum bits, we know that a quantum state does not change if we multiply it with any number of unit norm; i.e., $| \mathbf{\psi} \rangle = e^{j \xi}| \mathbf{\psi} \rangle$ Let’s set $\xi = -\varphi_0$. Then, our (equivalent) state is:

\[e^{-j \varphi_0} \cdot |\mathbf{\psi} \rangle = e^{-j \varphi_0} \cdot \left( r_0 e^{j\varphi_0} \cdot | \mathbf{0} \rangle + r_1 e^{j\varphi_1} \cdot | \mathbf{1} \rangle \right) = r_0 \cdot | \mathbf{0} \rangle + r_1 e^{j(\varphi_1 - \varphi_0)} \cdot | \mathbf{1} \rangle\]From 4 parameters, now we end up with 3 parameters! $r_0, r_1$ and $\varphi := \varphi_1 - \varphi_0$. It turns out we can do more: remember that $|c_0|^2 + |c_1|^2 = 1$. After easy algebraic manipulations, this translates into: $r_0^2 + r_1^2 = 1$, reducing the number of unknowns to 2! Using the angle representation of the above equality and setting $r_0 = \cos \theta ~\text{and}~ r_1 = \sin \theta$, we obtain the equivalent repsentation of $|\mathbf{\psi} \rangle$:

\[|\mathbf{\psi} \rangle = \cos \theta \cdot |\mathbf{0} \rangle + e^{j \varphi} \sin\theta \cdot |\mathbf{1} \rangle.\](A different interpretation of the above is that we care only about the relative phase between the two states, not their actual phase; thus, w.l.o.g., we can assume that one of the states has real coefficient).

The Bloch sphere representation

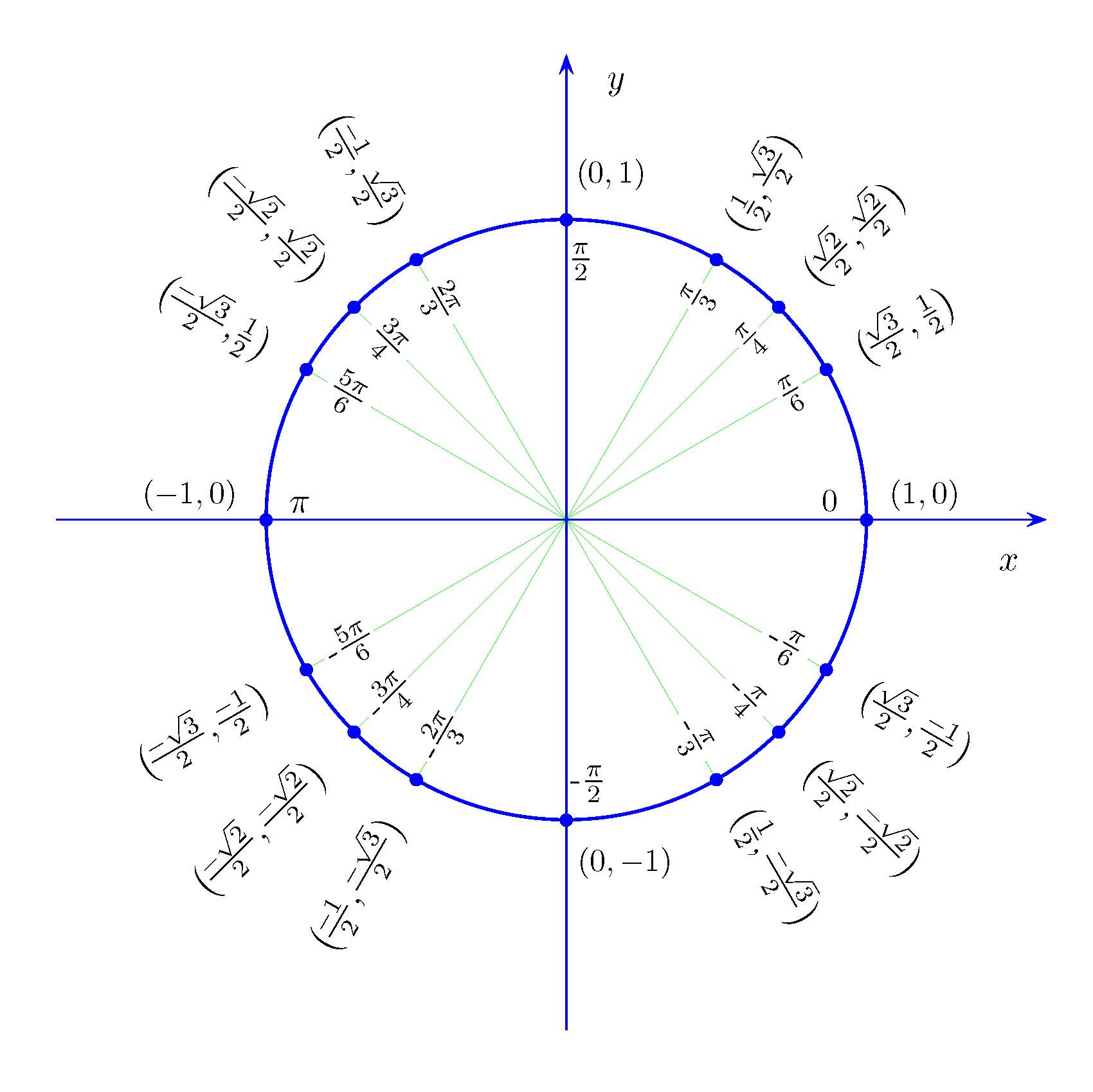

The above result into the Bloch sphere representation, named after Felix Bloch. This representaiton is a unit 2-sphere, where at the north and south poles lie two mutually This representation has a nice geometric perspective:

Due to equivalent representations of states via the Bloch diagram, any state can be written as: \(|\mathbf{\psi} \rangle = \cos \tfrac{\theta}{2} \cdot |\mathbf{0} \rangle + e^{j \varphi} \sin \tfrac{\theta}{2} \cdot |\mathbf{1} \rangle.\)

The range of values for $\theta$ and $\varphi$ such that they cover the whole sphere (without “repetitions”) is $\theta \in \left[0, \pi \right)$ and $\varphi \in \left[0, 2\pi \right)$. Angle $\theta$ corresponds to lattitude and angle $\varphi$ corresponds to longitude. Let’s see some examples.

- Assume that $\theta = 0$. This means that: $|\mathbf{\psi} \rangle = 1 \cdot |\mathbf{0}\rangle + e^{j\varphi} \cdot 0 \cdot |\mathbf{1}\rangle = |\mathbf{0} \rangle$. Now assume that $\theta = \pi$; similarly we get: $|\mathbf{\psi} \rangle = 0 \cdot |\mathbf{0}\rangle + e^{j\varphi} \cdot 1 \cdot |\mathbf{1}\rangle = e^{j\varphi} \cdot |\mathbf{1} \rangle = |\mathbf{1} \rangle$

- Assume that $\theta = \tfrac{\pi}{2}$ and $\varphi = 0$. Then, $|\mathbf{\psi} \rangle = \tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \cdot |\mathbf{0}\rangle + \tfrac{e^{j0}}{\sqrt{2}} \cdot|\mathbf{1}\rangle = \tfrac{|\mathbf{0} + |\mathbf{1} \rangle}{\sqrt{2}}$, while for $\varphi = \pi$, we get $|\mathbf{\psi} \rangle = \tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \cdot |\mathbf{0}\rangle + \tfrac{e^{j\pi}}{\sqrt{2}} \cdot|\mathbf{1}\rangle = \tfrac{|\mathbf{0} - |\mathbf{1} \rangle}{\sqrt{2}}$.

The Bloch sphere provides the following interpretation: The poles represent the classical bits, let us use the notation $| \mathbf{0} \rangle$ and $| \mathbf{1} \rangle$. However, while these are the only possible states for the classical bit representation (Disclaimer: someone could argue that, since the classical bit is represented via voltages, the classical bit representation contains also the axis connecting the two poles.), quantum bits cover the whole sphere. Thus, there is much more information involved in the quantum bits, and the Bloch sphere depicts that.

When the qubit is measured, as we have discussed already, it collapses to one of the two poles. Which pole depends exactly on which direction the arrow in the Bloch representation points to: If the arrow is closer to the north pole, there is larger probability to collapse to that pole; similarly for the south pole. Observe that this introduces the notion of probability in the Bloch sphere: the angle $\theta$ of the arrow with the vertical axes corresponds to that probability. If the arrow happens to point exactly at the equator, there is 50-50 chance to collapse to any of the two poles.

On the other hand, rotating a vector w.r.t. the $z$-axis results into a phase change, and does not affect which state the arrow will collapse to, when we measure it. This rotation is achieved by changing the $\varphi$ variable.

Manipulating the sphere

So far, we talked about operators (= Hermitian matrices) that “preserve the energy” of the system. A different way to see such operators is as transformations of vectors (here, we restrict our attention to a single qubit system) over the Bloch sphere. The $X, Y$, and $Z$ Pauli matrices (and their combinations) are exactly the matrices that rotate/invert representations on the sphere.

As their name suggest, $X, Y$, and $Z$ rotate a vector (or rotate the Bloch sphere) w.r.t. the $x$-, $y$- and $z$-axis respectively. These matrices result into 180 degrees rotations w.r.t. to the corresponding axes.

Rotations of a specific degree and w.r.t. different axis define a set of phase gates, as follow:

\[R_x(\xi) = \cos \tfrac{\xi}{2} \cdot I - j \sin \tfrac{\xi}{2} \cdot X = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \tfrac{\xi}{2} & -j \sin \tfrac{\xi}{2} \\ -j \sin \tfrac{\xi}{2} & \cos \tfrac{\xi}{2} \end{bmatrix},\] \[R_y(\xi) = \cos \tfrac{\xi}{2} \cdot I - j \sin \tfrac{\xi}{2} \cdot Y = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \tfrac{\xi}{2} & -\sin \tfrac{\xi}{2} \\ \sin \tfrac{\xi}{2} & \cos \tfrac{\xi}{2} \end{bmatrix},\] \[R_z(\xi) = \cos \tfrac{\xi}{2} \cdot I - j \sin \tfrac{\xi}{2} \cdot Z = \begin{bmatrix} e^{-j\tfrac{\xi}{2}} & 0 \\ 0 & e^{j\tfrac{\xi}{2}} \end{bmatrix}.\]These rotate the current state w.r.t. the corresponding axes by $\xi$ degrees.